Tax Planning: More Than Lowering Your Tax Bill

Tax planning is a fundamental part of financial planning. Yet, there’s a misguided notion amongst some members of the financial industry and individuals that the goal of tax planning should solely be about MINIMIZING your tax bill. While this may have some short-term benefits, in actuality, the goal of tax planning should be to MAXIMIZE after-tax net worth over your lifetime. Indeed, there are times when minimizing your annual tax bill aligns with maximizing your after-tax net worth, but not always. First, let’s review how taxes shape our savings.

The Impact of Taxes on Savings

There are three main types of accounts from a tax standpoint. First, you have your tax-deferred accounts. These are accounts such as the traditional IRA, traditional 401(k) and 403(b) amongst others. The basic idea is that the IRS allows you to save dollars pre-tax into these accounts— every dollar you put into one of these accounts is a dollar that goes untaxed that year. However, these dollars are not untaxed forever but simply deferred until you withdraw the funds. While you avoid taxes any year you put away dollars in a tax-deferred account, you are also creating a future tax liability that will be dependent on future tax rates.

Second, you have your tax-free (or tax-exempt) accounts. These are primarily represented by any Roth or Roth 401(k) accounts, but some specialty accounts have similar features. For example, Health Savings Account (HSA) for healthcare purposes or a 529 for college expenses. Whether you are using a Roth IRA or a Roth 401(k), dollars saved into these accounts don’t save you any taxes payable today. However, since they have already been taxed, they are allowed to grow tax-free and be withdrawn tax-free in the future. As an aside, the HSA actually allows pre-tax contributions and tax-free withdrawals for health care costs which makes them pretty special! 529s also often allow pre-tax contributions, at least at the state tax level.

Finally, you have your after-tax accounts. These would be most of your standard brokerage accounts and trusts (trusts can get quite a bit more complicated from a tax standpoint depending on what type of trust it is, but that would be another entire article, so we’ll keep it simple here). Unlike the tax-deferred and tax-free accounts, there are no limits placed on contribution amounts in any given year. Dollars contributed to these accounts receive no tax benefit in the present nor future. Growth of these savings is taxed at capital gains rates upon sale which are much lower than income tax rates, for most. In other words, if I buy a mutual fund for $10,000 and it grows to $30,000 by the time I sell it many years later, then I would owe capital gains tax on the $20,000 that my fund increased in value. However, as long as I don’t sell, I would not incur any taxes on the gain for all those years of growth.

Now that we have reviewed the different ways taxes can impact our savings, let’s look at how tax planning can help achieve our goals.

Tax-Deferral Is Not Always King

For a long time, the conventional wisdom has pointed to tax-deferred accounts as the most effective way to allocate your long-term savings. The idea being that you forego paying high tax rates while you are earning those dollars and then pay lower tax rates upon withdrawal when you are in lower tax brackets during retirement. This relies on two big assumptions, though. First, that you end up in lower tax brackets in retirement and second, that tax rates remain unchanged or are lower in the future than they are today.

We have found that this first assumption isn’t always true for some. Via their portfolio, Social Security, and perhaps a pension or two, many clients find themselves with income in retirement that keeps them in relatively similar tax brackets as when they were working.

One example of this would be a couple who put all of their savings into their 401(k) over the years. They certainly paid fewer taxes over their working life during this time, but now have $3 million all in tax-deferred accounts. Well, if they want to live off of $100,000 per year, they may have to withdraw about $130,000 per year to do so since each withdrawal will be taxed. They are also at the mercy of changing tax law and the potential for higher future brackets.

To that point, the second assumption about future tax rates is also something worth challenging depending on your age. I’m in my mid-30s and though there is much uncertainty about what tax brackets may look like in 30 years, the assumption that they may be lower than today’s historically low brackets may be a bit of wishful thinking.

Thus, we find ourselves often advising clients to contribute to a Roth 401(k) instead of their traditional 401(k) in certain years. In some cases, it may even make sense to contribute to an after-tax account in lieu of a 401(k). Perhaps there are high embedded fees or undesirable investment options in their company’s retirement plan, for example. Each client situation is unique and so is each tax year, so it’s an ongoing process to figure out the most efficient way to save.

Retirement Withdrawal Strategy

For those with a large part of their net worth in tax-deferred accounts (401(k)s, traditional IRAs), there is a looming tax liability on the horizon in addition to ongoing withdrawals—the required minimum distribution (RMD). At age 72 (previously RMD age was 70.5, but recent legislation moved it back to age 72), the IRS requires that you start taking out a portion of your IRA every year and paying taxes on the withdrawal. At age 72, the requirement is a roughly 4% withdrawal and it goes up from there, so a client with a $2 million IRA would generally have to withdraw around $80,000 in that first RMD year and pay the associated income taxes.

Rather than waiting for the clock on that ticking time bomb to hit zero, there are strategies available prior to age 72 that might improve after-tax net worth. Let’s look at an example.

Sue is a 62-year-old retired individual with $20,000 in income from an old pension and has not started social security yet. She has a large after-tax brokerage account and a large IRA from the 401(k) she rolled over to support her retirement. If the goal was to minimize her taxes in any one year, she would spend the money in her brokerage account first so as not to incur any taxes from withdrawing her IRA. However, since we know the better strategy is maximizing after-tax net worth, one idea would be to take the first $20,000 of her retirement needs from the IRA. That would result in about $40,000 in income, but keeps Sue in the 12% federal tax bracket. It is quite likely the 12% she pays on those funds will be far less than letting her IRA continue to grow aggressively and paying taxes a decade from now when she must make large withdrawals. The rest of her needs could come from her after-tax brokerage account where she may pay some capital gains taxes but those would be at much lower rates.

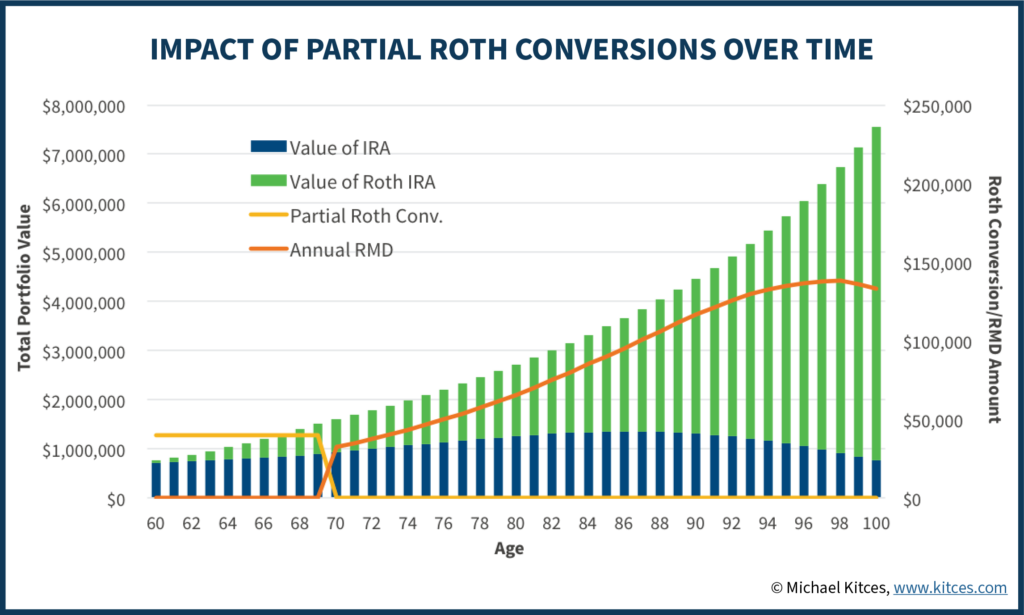

Roth Conversions

Similar to the strategy of Sue, but with a different end goal, is the idea of Roth conversions. We’re still going to utilize the idea that we can pull out some dollars prior to age 72 from our IRA and stay in a relatively low tax bracket. However, instead of spending it, we’re going to convert it to a Roth IRA, similar to the chart above. That means we incur taxes today on the funds we’ve pulled out of the IRA, but all future growth will now be in the tax-free Roth account. It can take a while for the effect of the tax-free growth to make up for the taxes paid, but in the case where this money is likely to be distributed via inheritance(s), it often makes a lot of sense. Of course, you would need to get over the fact that you are essentially pre-paying your children’s taxes to do so. As a father of a six-year-old and three-year-old, let me just say that they have some more work to do over the next few decades to earn these gifts!

Rebalancing and Portfolio Repositioning

Another reason to incur taxes today is simply due to changing markets. In this case, I’m specifically talking about an after-tax account and realizing capital gains by selling assets. There are often cases where we don’t want the tax tail to wag the dog, so to speak. Two scenarios come to mind:

First, perhaps you are holding an expensive mutual fund or an individual stock that has embedded gains, but it does not align with the best long-term, low-cost and diversified portfolio thinking. It could make sense to sell, incur the capital gains taxes, and reinvest in something that will serve you much better long-term.

The second reason that comes to mind has been quite relevant this year. With the rapid growth of the stock market following the initial crash from the onset of the pandemic, many clients developed large gains. They also found that their portfolio allocation mix had started to drift towards a higher percentage of risky stock assets. We’ve praised the idea of rebalancing back to target when needed in other articles, but a side effect of rebalancing is that you do occasionally incur capital gains to do so. Barring special circumstances, the cost of capital gains tax is almost always worth it when rebalancing is needed to make sure you’re at the appropriate risk tolerance going forward as markets will inevitably have their corrections along the way.

Changing Tax Rates

As of this writing, there are new tax proposals being debated and by the time this goes to print, I imagine we’ll know much more. However, changing tax rules can sometimes be a reason to incur taxes in a year.

The easiest example is the case where we know income and capital gains tax rates are set to rise the following year. In that case, if this change will impact investors in your tax bracket, it might very well make sense to “harvest capital gains” now at the lower rate or convert more IRA dollars to Roth accounts knowing our tax liability will be greater in the future. It is always best to discuss your specific situation with your advisor when considering decisions related to changes in tax legislation to ensure that they make sense for your long-term plan.

Changing the Perspective

The goals of tax planning should be to get us closer to our overall goals and purpose, like every other financial decision we make. Shifting our focus to maximizing our after-tax net worth over our lifetime instead of pure tax avoidance in the short-term is a great tool to allow us to get to our destination quicker and more efficiently.