Well there’s a loaded question! It’s certainly one worth asking, though, given the roller coaster ride of the last six months. To answer that question, we need to take this on in two parts. First, we need to define risk. Second, we’ll determine how you can analyze the level of risk appropriate to your situation.

The Definition of Risk

Ever since I started working in this industry, a huge pet peeve of mine has been how we describe risk. Traditionally, risk is defined in terms of portfolio volatility—the greater the potential for day-to-day fluctuation of a portfolio, the greater the risk. Indeed, it is this risk of short-term volatility that is related to our long-term expected returns. The more short-term risk you’re willing to tolerate, the higher your future expected returns.

Indeed, this definition is appropriate when you are talking about dollars you’ll need in the relative short-term. If you plan on using your investments soon, then there is significant risk taken when you allow that money to be invested in volatile assets. On the other hand, none of us are using all of our money tomorrow. Whether you’re just starting to save or you are well into the withdrawal phase of your life, you have different buckets of money: the money you’re using soon and the money that’s for later. The size of those buckets will vary greatly from person to person, but we all have both.

Daily portfolio volatility is a fine definition of risk for our short-term bucket, but it’s a terrible definition when it comes to our long-term bucket.

For long-term dollars our actual risk is not daily volatility, but that we may fail to accumulate enough to keep up with inflation and fund our long-term goals. If you focus too much on daily volatility when it comes to this bucket, you can end up making some very bad decisions. For example, including a significant portion of fixed income into your long-term assets actually increases your risk of not keeping up with inflation or accumulating enough over the next 30 years even though it lowers the short-term volatility.

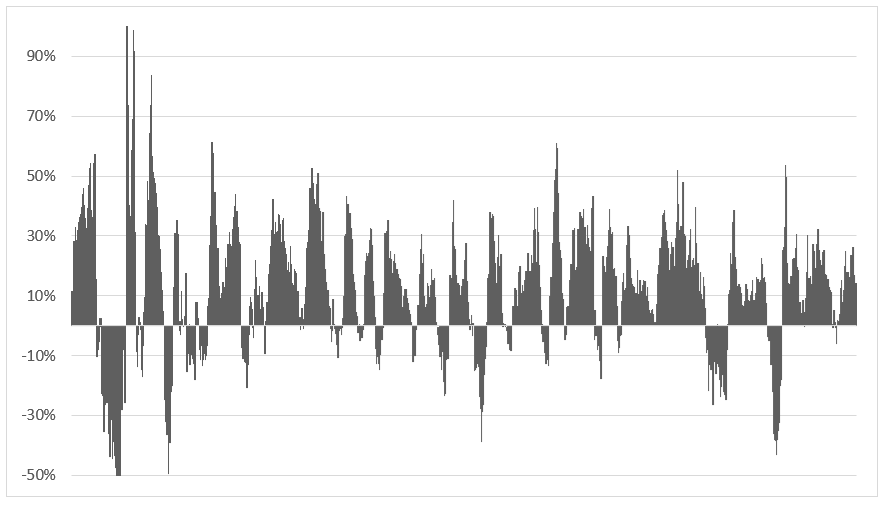

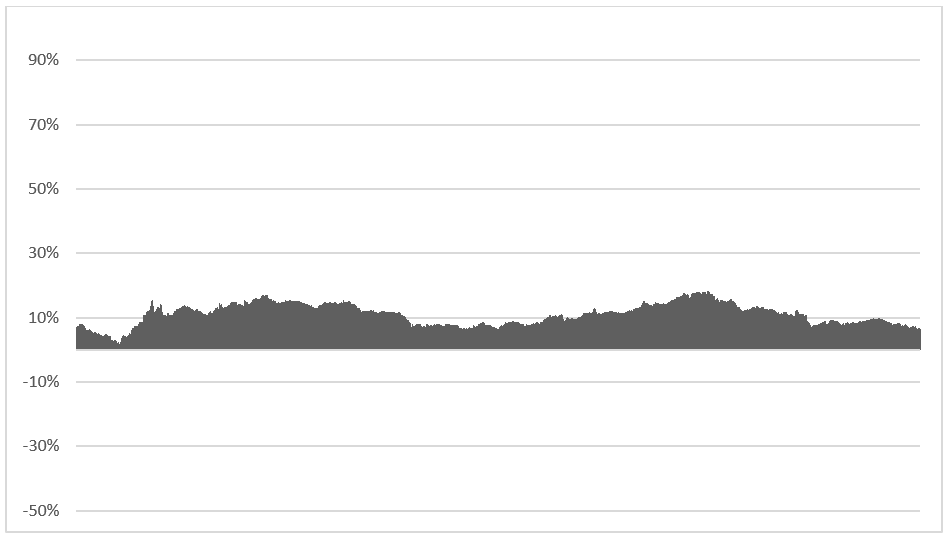

I think it’s helpful to show a couple of charts. First, here’s the annual volatility of the stock market as represented by the S&P 500.

That is definitely not something we should be interested in putting our short-term dollars into. However, let’s look at rolling 20-year returns of the stock market:

So am I really putting my money at risk by investing in the stock market if that money is long-term? The traditional definition of risk would say yes because of Chart 1, but we can see that’s not really the case. It’s crucial that we define our real risks appropriately.

How do I determine my overall risk?

Put another way, how do I determine how much I should have in my short-term bucket and how much should I have in my long-term bucket?

There are three components that should factor into determining the appropriate portfolio allocation: your ability to take on risk, your willingness to take on risk, and your need to take on risk.

Your ability to take on risk is largely determined by the time frame of your goals. A young investor with twenty years until retirement has a high ability to take on risk. Short-term volatility in that case becomes largely irrelevant as we saw in the chart illustrating twenty-year returns. That investor has the ability to put most of their money in their long-term bucket. On the other hand, an investor focusing on a college fund for their 17 year-old child has much less ability to take on risk. The ability to weather volatility is severely reduced in that instance and most of the money should be in a less volatile short-term bucket.

Your willingness to take on risk is much more subjective and ties into the behavioral aspect of personal finance. If you’re the type of person to lose sleep when your investments are losing value, then that’s pretty important to know. Perhaps you’ve run across a “risk questionnaire” at some point. Those actually address the willingness component fairly well, but unfortunately are often presented as all encompassing. Using just a risk questionnaire is an incomplete way of picking a portfolio allocation and it’s what a lot of Wall Street firms do. Naturally, that leads to me poking fun at them.

Are you risk-tolerant? Or are you risk-averse? How risk-averse are you? Do you feel anxious if your investments lose value? Has your appetite for risk increased or decreased over the last five years? Have you ever been skydiving or scuba diving? If your investments lose 32% of their value in one year, are you more likely or less likely to cash out your investments, sell your home, ditch your family, and establish a gardening commune high in the mountains?

Okay, I may have embellished that last one, but these are fairly standard questions, and you can see how they may help you work through your own willingness to accept risk. As long as you use the questionnaire with the understanding that it is gauging just this one component of your risk decision, then they can actually be somewhat useful. Just remember to weigh the results accordingly.

Lastly, and most importantly, you must establish what level of risk you need to take in order to meet your goals (see here for the goals that matter). As we established earlier, short-term volatility is directly related to long-term expected return. Lofty goals may require high returns and a corresponding high level of risk. For example, a retiree may have a strong desire to double or triple their assets for inheritance which would require more short-term volatility in an effort to capture higher returns and achieve the goal. Conversely, the same retiree may have no desire to leave an inheritance and require only a 2% withdrawal rate from their assets to comfortably live the lifestyle they would like. That client would need little risk, if any, in order to meet their goals. Most of their money could be in a less volatile, short-term bucket.

When the components are not in alignment.

Ideally your ability, willingness, and need to take on risk will match, but serious conflict can arise when these three components are not in sync. Perhaps you’re young (high ability) with the goal of early retirement at an elevated standard of living (high need), but you’re very uncomfortable with any short-term drops in portfolio value (low willingness). This will probably result in either a reevaluation of your goals since they aren’t achievable with a low risk portfolio, or an alternate solution (save a lot more now).

In another scenario, maybe you’ve underfunded the education account for your child and now they’re a junior in high school and will be using that education money up in the next five years. You have a high willingness and a high need to take on risk, but your ability to take on risk is relatively low.

There are rarely easy answers when the three determinants or risk are in conflict. However, with a clear understanding of how each applies to your situation and by planning early and often, you’ll have the best information available to make an educated decision. Obviously, your TCI advisor is here to help with that.

The last six months have put the idea of risk back at the forefront of our thinking in more ways than one. It’s important to balance how we rate on each component of risk while also keeping in mind that we all have multiple buckets of money, even though we may not view it that way typically. A solid understanding of the risks that matter with each bucket helps us stay the course in the face of increased volatility, and that’s the best way to achieve what we want.