How much is enough money?

It’s a complicated question, without a doubt, but there are several ways we can approach it. We can address it philosophically in the context of a big picture discussion along the lines of “what is the meaning of life?” or “how do you define happiness?” Then there is the more tactical approach by way of quantifying a dollar amount relative to a target goal or monetary need, “how much does it cost simply to live?” or “how much do I need to fund my present lifestyle?” In the middle of that spectrum is the kind of question along the lines of “can money buy happiness?”

Of course, there is no uniform answer. In fact, the question alone is unique to the individual. One person’s “normal” is another’s dream life. What makes you happy? How much does that cost?

Money Can, in Fact, Buy You Happiness

I can say with certainty that the maxim “money can’t buy you happiness” is not entirely accurate. Of course, you can’t go to the store and pick up your favorite brand of “happiness,” but we all know that. Money does, however, give us the ability to purchase food and shelter, tools to help us be productive, the means to increase our standard of living, and even a sense of security. Our ability to be happy relies in part on being able to fulfill certain of these basic human needs. It is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs at play.

The saying should go “all money can’t buy happiness… but some can.” I say that because I agree with the notion that unlimited money will not make you happy, but I am cognizant of the reality that a certain amount of money does give us the ability to meet basic needs, at which point we begin to have the psychological capacity to be happy, up to a certain point. Beyond that, we have to look elsewhere for our happiness.

The Utility of Money

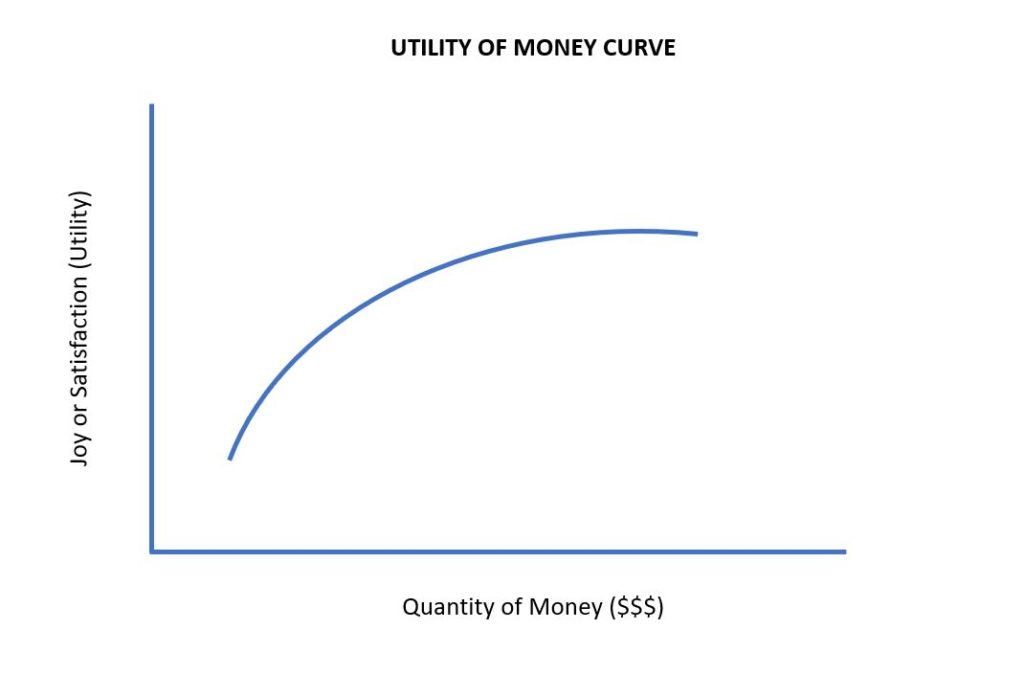

A foundational concept in microeconomics is the utility of money. This idea posits that more money is

better than less money. It does, in fact, mean that more money makes us happier. But the amount of happiness that we feel when we receive more money is proportional to the amount of money that we already have.

Let’s use $100 for our discussion. If I have no money at all, $100 will make me very happy. With $100 I can by food and clothing. I can survive. In this case, if I have no money to begin with then $100 can literally mean life itself. Every dollar of that $100 makes me very very happy.

Now let’s say that I have $1,000, enough money to buy food and clothing on a regular basis. $100 at this point is not the difference between life and death, but it can change the game for me. With $100 I can afford to buy transportation, which gives me more options and more opportunity. $100 is not quite as good as life itself, but it does make life better for me, and that makes me very happy.

You can see where I am going with this, but I’m committed to following through with one further example to complete the illustration. Now I have $30,000. I can buy food and clothing, transportation, and I can choose where I live, to a certain degree. $100 now gives me the ability to save for the future, go out to a nice dinner with a loved one, buy a nice sport coat for work or the next job interview. With $30,000, my options for every $100 are exponential compared to when I had no money or even $1,000. These options do make me happy, but their consequence, or utility, are far less significant.

Roger Kay describes the concept of the utility of money nicely in an article that he wrote for Forbes:

The story in the curve is, the more money you have, the less useful another dollar is. That is, the gain in utility is ever-so-slightly smaller with each additional dollar. The chart makes perfect sense in Maslovian terms. The first dollar you obviously use for food, the next, for shelter, then clothing, and so on. By the time you get to your millionth dollar, you are presumed to be spending it on a Maserati, and at your billionth, you might be outfitting a nice boat or snapping up an island the way Larry Ellison, CEO of Oracle, has done. The idea is, those marginal dollars are less needed. I mean, how many boats can you sail? In fact, some of the younger, more radical professors hypothesized that the curve really looks like this: where, at some point, additional dollars have negative utility. That is, it’s more of a headache to manage, maintain, and otherwise deal with more money at some arbitrarily high level than it is a benefit to have it.

There is a popular lesson taught in introductory economics classes to illustrate this point in real time. Teachers will bring in a popular food item—pizza, donuts, chicken tenders, etc. Students will be offered unlimited pizza, for example, to participate. They then proceed to rank the satisfaction of each piece they consume. Students are excited at the prospect of free food, and naturally hungry. The first one-to-three slices get the highest marks for satisfaction, but after a certain number of slices, that next slice is not as satisfying. Each successful slice of pizza consumed is accompanied by an exponential decrease in satisfaction, with the decrease in rating getting more extreme with each slice and even with each bite.

At what point does the $100 lose any sort of significant value? That is not for me to decide. Each person will reach this point at a different time, but the utility of money curve remains the same for everyone. More money is certainly better than less, but the more money that you have diminishes the happiness, or significance, of that next dollar.

The Concept of Enough and Utility Found in Philanthropy

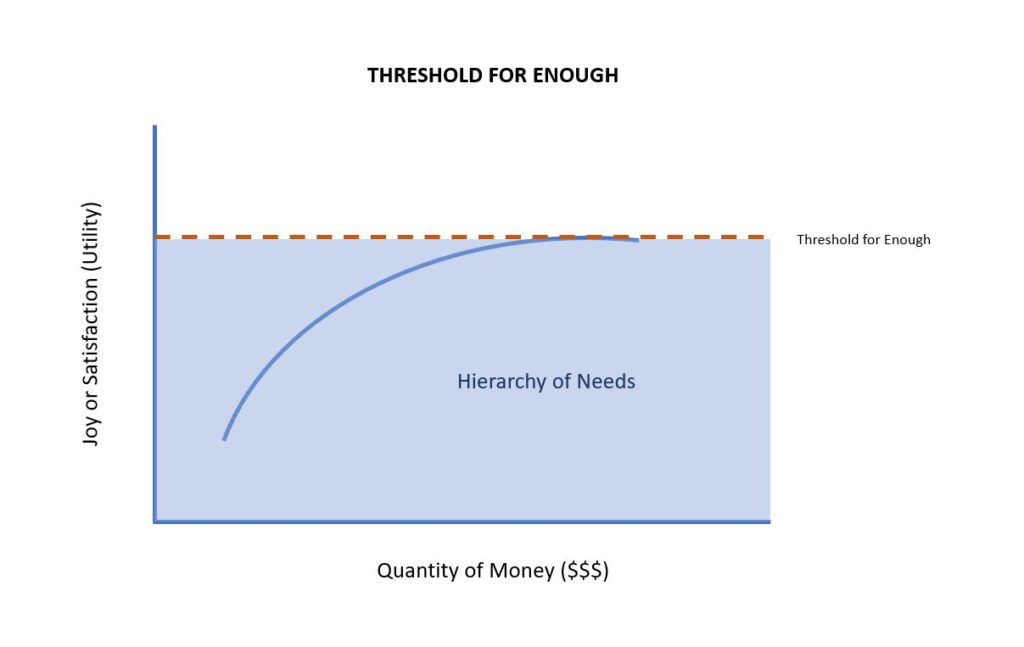

The utility of money curve makes sense mechanically, but it only addresses meeting the needs of oneself and fails to account for the value of addressing the needs of others. What I am saying, and what the utility of money is really getting at, is that we all have a threshold for enough. Once we reach that threshold, once we have satisfied our needs hierarchy, our capacity to benefit, both intrinsically and extrinsically, diminishes regarding our own needs.

There is a reason why it is impossible to argue against the idea that “there is no such thing as a selfless act.” Helping others makes us feel good, especially when our own needs are already met.

In a report published by the Women’s Philanthropy Institute at Indiana University, Charitable Giving and Life Satisfaction, researchers make the case that there is a direct positive relationship between philanthropy and life satisfaction.

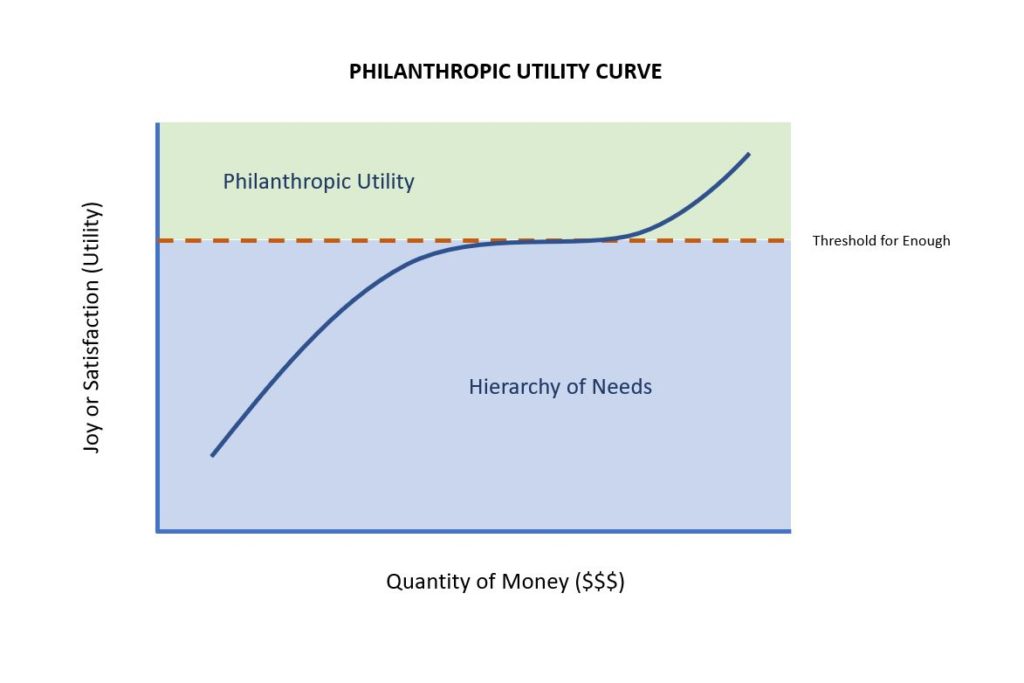

Consequently, the utility curve in its traditional form is incomplete. There is a way to extend the upward slope on the utility curve such that each successful dollar will continue to have meaning and drive happiness beyond the point at which it begins to level out and diminish. Simply put, once you have met your threshold for enough, you will not gain any sort of utility, satisfaction, or happiness by keeping that next dollar, but you will gain all those things by giving it away. I call this philanthropic utility.

I recently met with a couple who are selling their business for a significant amount of money. By their own admission, the sale value is well beyond their own threshold for enough. They have actively planned to share in the profit from the sale with every employee at the company, and they are also putting into place a very generous charitable giving plan. When they talk about their own financial plan they are engaged, sure, but they really light up when they start speaking about their plans for giving to their employees and to charitable causes. When we have these conversations, I can physically see the progression of the utility curve slope up and into the realm of philanthropic utility. They get real joy out of their ability to help others. Furthermore, their wealth takes on more meaning, for them and for others. At one point in our last conversation, they said that they “are fortunate that their wealth can be such a blessing to others.” I found those words to be deeply moving.

They’re not the only ones. Majority of our clients at TCI are, or want to be, able to extend the utility of their wealth in very rewarding ways. In fact, one of our goals is to get people to a place in their financial lives where they can make that progression themselves. It is one of the important ways in which we do financial planning, looking beyond what is right in front of us and finding meaning in more robust ways that may be less obvious. TCI’s CEO, John Stephens, makes a nice case for this in an article he wrote a few months ago, The Triumph of Resilience in a Pandemic. “There’s plenty we can do to soften the harsh edges of these hard times. Figure out what you can do to help in your family, your workplace, your community—then do it. “