The stock market is hitting new all-time highs and with that I’ve noticed increased nervousness amongst investors. This is a welcome change—as Warren Buffet once said, “Be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful.” Nevertheless, it’s a good reminder for us to take a look at what your true risk is as a long-term investor.

I’ve pointed this out before, but it’s always struck me as odd that the industry talks about return from a long-term perspective and risk from an extremely short-term perspective. For example, your long-term returns in an all-equity portfolio would have been around 10%, but with the “cost” that some of the single worst years saw a drop of 40-50%. Does that single worst year matter though? If you’re investing money that won’t be touched for 10+ years, does it matter what happens this year or next? The answer, of course, is no, but we’re constantly led to believe that one year downside is a relevant measure for us to think about.

Your true risk is an extended period of 15+ years where stock market growth for a globally diversified portfolio is much lower than what we’ve come to expect; we refer to this as generational risk. The bad news is that generational risk is completely out of your control. The good news is that because it’s completely out of your control, you can focus on factors that can mitigate the impact.

A Balanced Portfolio Can Reduce Risk

First, as it directly relates to your investments, you can follow a disciplined strategy of rebalancing. A “flat” stock market is never really flat. It swings up and down even though it ends up in the same place where it started—the S&P 500 from 2000-2013 is a great example:

Simply buying the S&P 500 and holding for those thirteen years would have resulted in little growth of wealth. However, we don’t just hold the S&P 500. A well-diversified portfolio should hold small stocks, international stocks, and likely fixed income in some capacity. A disciplined rebalance strategy would sell the relatively well-performing assets and buy the relatively poor-performing assets. You won’t hit the mark exactly right each time, but you will more often buy low and sell high and you can generate modest wealth growth even in a longer-term “flat” market.

Far more significant than what you can do with the portfolio is what you can do with your behavior in two important ways. First, don’t let panic or greed get the best of you along the journey. Short-term volatility will only significantly affect your plan if you react poorly to it and do the opposite of what a disciplined rebalance strategy would have you do. Second, you can always control your spending and saving. The greatest protection against generational risk is to spend less and save more.

Long-Term Growth is Slow but Powerful

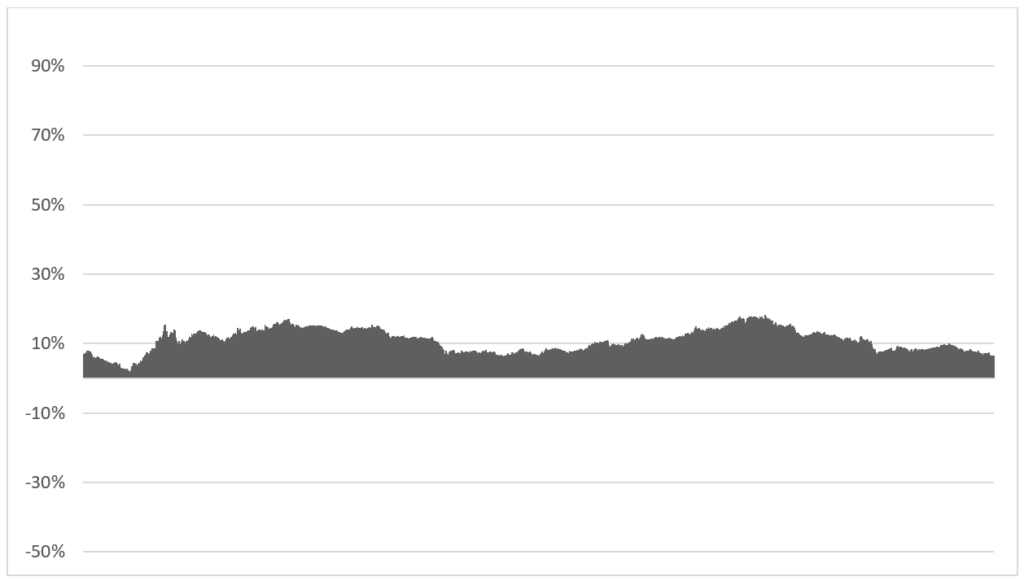

Knowing that the real risk to your plan is anemic long-term growth should be somewhat freeing. There’s no need to worry about what will happen next year in the market because your plan is predicated on bad years occasionally happening in the market. Take a look at this chart of 20-year returns:

That looks like a “risk” I should be willing to take for my long-term dollars.