This Time Should be Different

Twentieth century investor, Sir John Templeton, is noted for saying that the four most expensive words in the English language are “this time is different”. No one is immune from the nagging sentiment that fundamentals have changed because of recent history. By “recent history” I am not referring to the last five to ten years. I am talking about “recent history” relative to any point in time since… well, any point in time.

Even the most ardent long-term investors, historical analysts, and market experts stop at points to wonder if the rules have in fact changed. Show me an “expert” who claims total immunity from this and I’ll show you the image of false bravado. All the data, the logic, the experience, and rational thinking is not enough to hold back the tide of doubt — at least a small sense of an imbalance in the force. This can be both emotional and academic.

Of course, when asking that question — “Is this time different?” — we instinctively want the answer to be “no”, and we look to the economic and market data to confirm that the rules are still intact. The timing is never certain, and we may experience a correction (short-term), a recession (less short-term), or a depression (long-term), but the market and the economy have always come back.

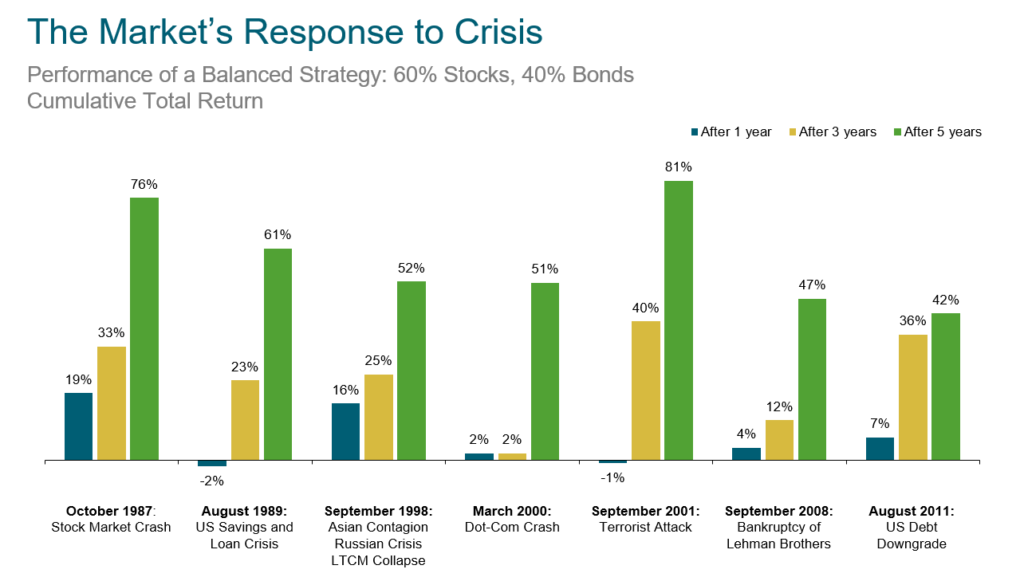

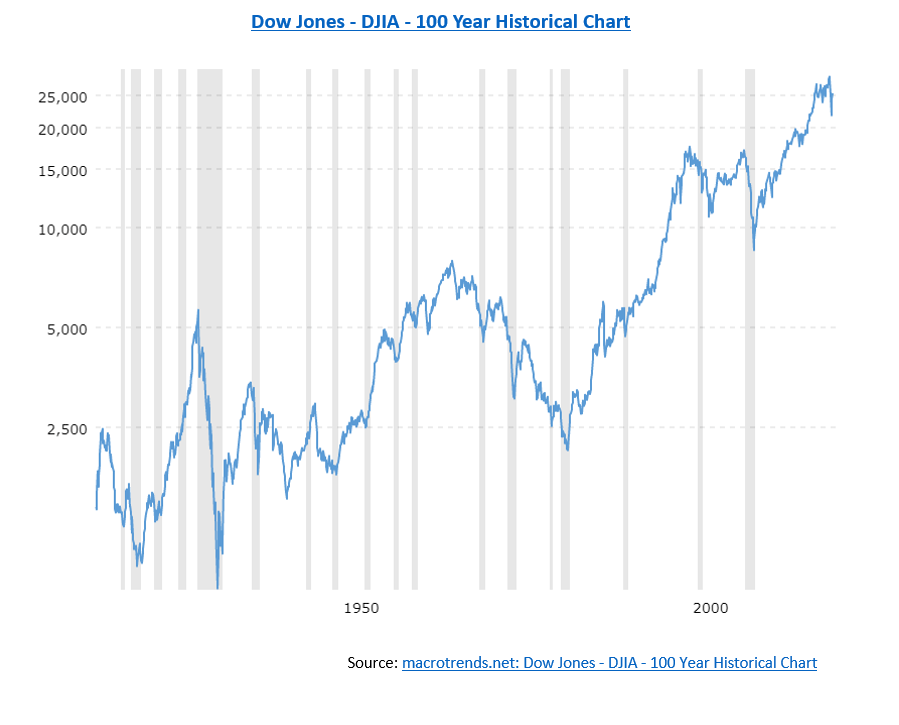

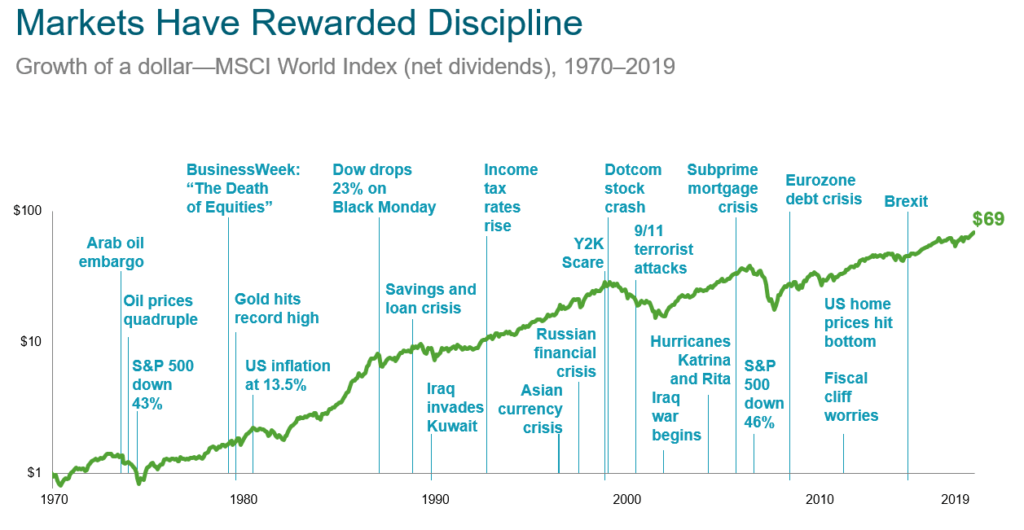

The data speaks for itself. Take a look at the following two charts. The first, provided by Dimensional, illustrates portfolio performance in reaction to market crises in the past 30 years. The second chart is a historical depiction of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, provided by Macrotrends, dating back to 1915. Strictly at the macro level, you can see positive returns over the long-term.

All of this is to say that the world is known for being quite good at making headlines, and the markets are resilient in spite of that fact.

But this does not mean that this time is not different. In fact, this time is very different, and that’s a good thing.

This Time is Different — Good

Humans are naturally averse to change. They just don’t like it. In fact, the brain is hardwired to resist change. The research on the neurobiological effect of change in humans is too robust for us to get into the details here, but trust me, it’s all there. (Hate to say this, but… Google it.) Simply put, we want to believe that nothing has changed and that this time is no different than all the others. That makes us feel the most at ease and secure. The moment we say “this time is different,” we have to admit to ourselves that change is afoot, and we automatically go into survival or adaptation mode.

But you can’t tell me that the world doesn’t change in response to historical events. The world, along with its economies and markets, was different after the Great Depression, World War II, 9/11, and — yes — coronavirus. The world was different when we tore down the Berlin Wall, when the internet came into play, and when the banks were, in fact, not “too big to fail” in 2008-09. The Civil War, the Industrial Revolution, the Sixties (the entire decade), the Exxon Valdez oil spill, Nelson Mandela and the end of Apartheid, Enron, and Occupy Wall Street.

In every instance, the market reacted and recovered from the consequent volatility. And the market — just like the world itself — also changed, for the better. The reason is explained by a concept known as Market Pull Theory.

Market Pull Theory

One of the key elements in a capitalist market is its innate ability to adapt. In other words, the market will identify a problem, or a demand, and consequently adapt by finding a solution and developing a product to meet that demand. This is known as Market Pull.

Similar in nature is the idea that new technology begets new technology. For example, Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs of Apple built the first personal computer (new technology), creating a demand for the modern laptop (new technology). This in turn allowed for the market to meet an endless array of demands throughout the last two decades of the twentieth century. Now think about the exponential growth created by computer and internet technology in the early twenty-first century. Each new product has the potential to spawn any number of capitalist offspring, thereby increasing the market’s capacity to grow. New products and innovations have this effect and so do social and economic events, such as war, elections, and political turmoil. They all generate new problems and, therefore, new demands that the markets are poised to meet.

Each time a historical event (good or bad) occurs, the market is left to sort itself out. There are winners and losers at the macro and micro level. In many cases, entire new industries and sectors emerge. Take the World Wide Web and the Dot Com bubble in the 1990’s as a prime example. How could the markets not experience some level of fundamental change in reaction to these events and new technologies? They can’t, and so they do.

So what happens when there is no change. What happens when “this time” is not different? Given Market Pull Theory, can no change ever really happen?

There is one distinct period in history that we can look to for a little insight on this: a 500-year stretch know in the western world as the Dark Ages.

Dark Ages and Dark Markets in Western Civilization

Now before the earnest historian storms out of the room in a rage, let me be clear by saying that the Dark Ages is in large part a mischaracterization of the era by scholars from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance who were essentially literature snobs and unsatisfied with the quality of the arts produced in the 500 years following the fall of Rome. A lot of good things happened in Europe between the 5th and 10th centuries.

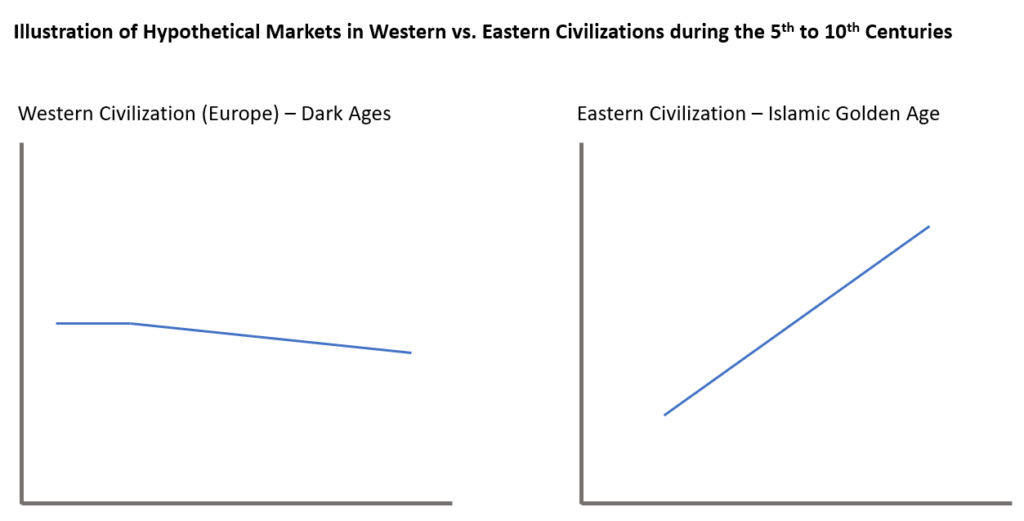

That being said, when Rome fell, the west lost its hub of technology and innovation, and an age-old culture of advancement in the arts and sciences spawned by the ancient Greeks and Romans went missing. Where once a powerful civilization built on a culture of innovation and scientific advancement you can see the effects of early Market Pull Theory. When the Roman empire was fragmented, so too were its markets, communication systems, and ability to effectively exchange information. For the next 500 years, in the ways of market innovation and new technologies in the west, essentially nothing changed. There wasn’t anything new of any relative value and the period was marked by technological stagnation. In effect, the lack of new technologies — or at least the widespread ability to share in them — was cause for decrease Market Pull, whereby markets created less demand on themselves and at the same time did not have the capacity to develop new products.

In other parts of the globe during the 5th and 10th centuries, particularly in the Arab world, advances in math and science were incurring at such a rapid pace that societies experienced what had come to be known as the Islamic Golden Age. Market Pull was very much in effect and advancement was so profound that these discoveries and breakthroughs played a major role in bringing Europe into the era of the Renaissance. It is a wonderfully stark illustration of the effects of no change (limited Market Pull) in comparison to “this time is different” (Market Pull).

Today our global economy is so intertwined that cultures and markets are dependent on each other, but we are able to see the effects of “this time is different” and “nothing has changed” by looking to the past when entire civilizations were still relatively isolated from one another (at least their markets and economies were more independent).

We don’t have data on ancient markets in the way that we do today (think Dow Jones and S&P 500), but we can envision what that might look like:

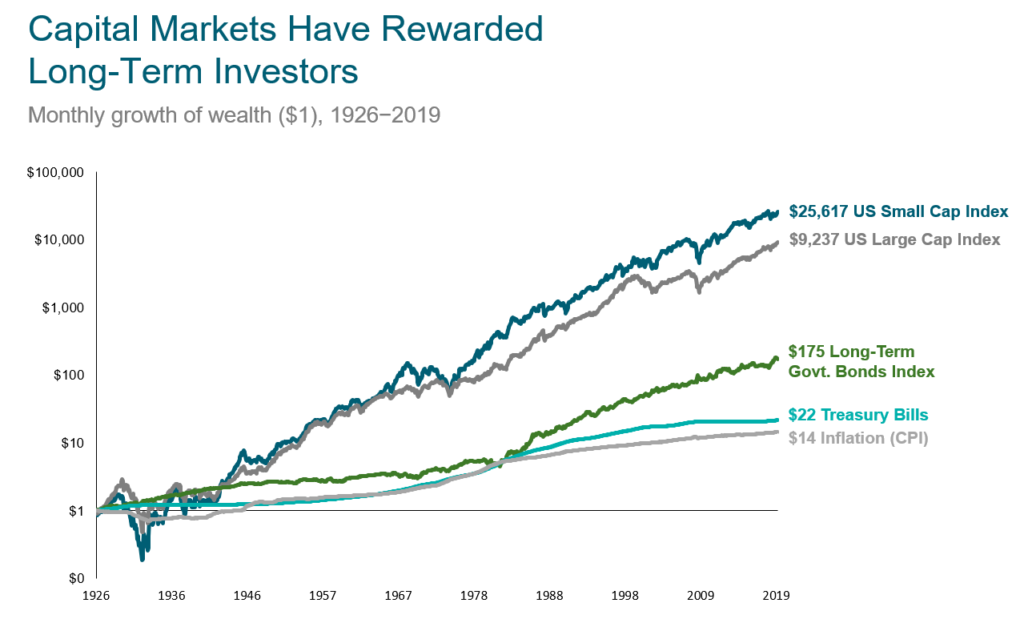

Now let’s compare these two charts to capital markets dating back to 1926 (provided by Dimensional):

No change versus “this time is different”. Templeton was right, those are the four most expensive words in the English language… because if we don’t embrace change and the Market Pull then we are going to lose out on a tremendous amount of wealth — and even risk going backwards.

Markets Do Change, and Investors are Rewarded for their Discipline

Templeton was really referring to the negative consequences that occur when investors ignore past data and make irrational decisions. Emotional investors use “this time is different” to justify an action that is counter to a disciplined approach to investing and the belief in efficient markets. But “this time is different” should not trigger a fear response or lend justification to an ill-advised portfolio decision.

Rather, we should respond to “this time is different” with “Good”. The fact that markets and economies are responding to global events is a good sign that the principals of Market Pull are still sound, and we can expect new demands, new products, and therefore long-term growth. The key point, here, is that markets reward discipline (provided by Dimensional):

The fact that our world is in a constant state of change — and always has been — is the very reason why Market Pull will continue to affect global markets positively in the long-term. Certainly, short-term turmoil and volatility are uncomfortable, but change is what moves all things forward.

Things are always better on the other side of a challenge. Market Pull helps us see to that. So I’m going to expand on Templeton’s famous words and change the mindset: “This time is different… Good. The future will be better.”