One of the silver linings to all of this is that I’ve gotten the chance to spend more time with my two-year-old daughter and four-year-old son than I otherwise would have. Of course, as other parents know, spending more time with kids now also requires that we take on the role of teacher. In my case, it’s relatively simple as we basically just get to mess up our driveway with sidewalk chalk and play outside in nature—I feel for those of you trying to hold a sixteen-year-old accountable to their trigonometry homework when they just want to sleep for twelve hours!

In this spirit, I thought I would put my “teacher” hat on and go back to the basics of investing over the next few weeks. A foundational understanding of why we take the approach that we do can be even more helpful than usual in volatile times.

There are two fundamental building blocks of investing that I want to focus on:

- Every transaction has a “winner” and a “loser”.

- Short-term risk and long-term return are related.

Regarding number one: if I sell a stock to you for $10 then one of us has to win that transaction—the price will go up and you win or the price will go down and I win. Why is this so important? It establishes real stakes for the market. People bet their expectations with real money, which leads to incredibly efficient price discovery and also forms the basis for the efficient markets hypothesis (more on that later).

Now on to number two: efficient markets can lead to significant short-term volatility for any asset as information and expectations change. For the chance at achieving long-term returns that outpace inflation and increase wealth, an investor must be willing to accept short-term volatility. In other words, if short-term volatility did not result in long-term returns, then investors would stop bothering with it—why sit through the pain if there is no reward at the end?

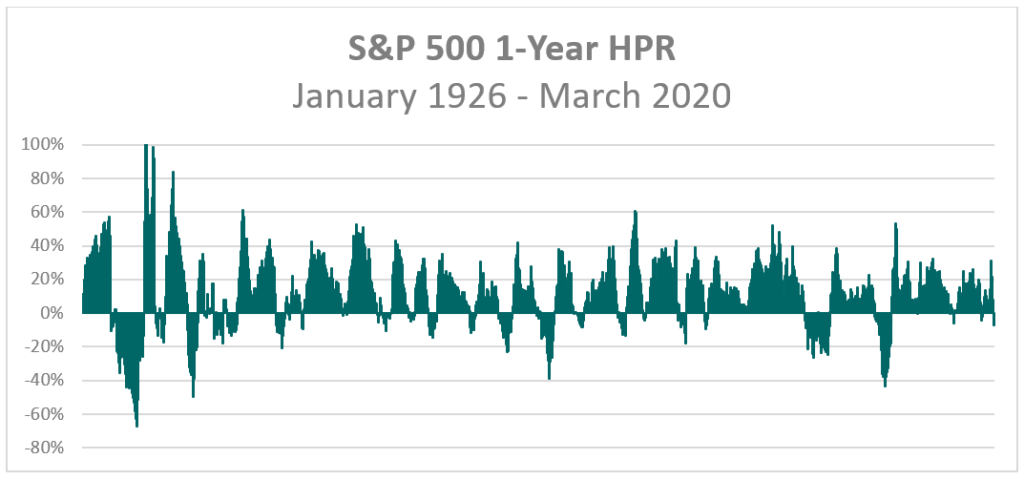

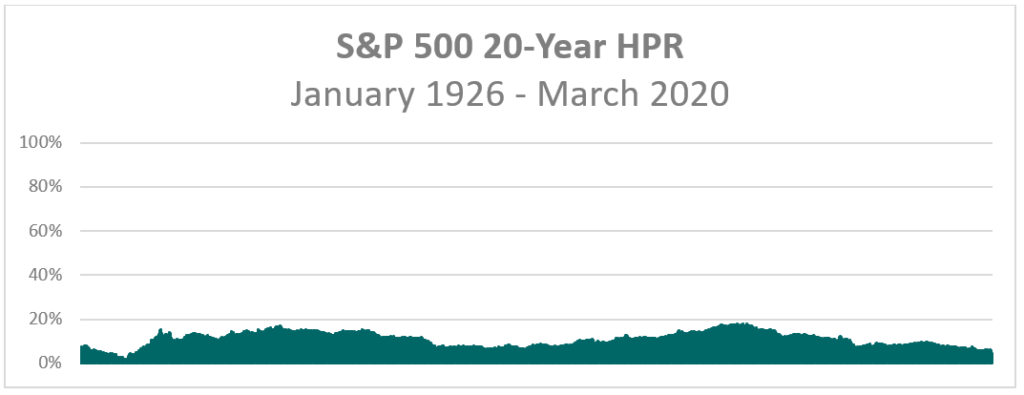

The good news here is that it is only short-term risk that we must tolerate to achieve long-term returns. Note that there is much less discrepancy in twenty year returns than one-year returns (HPR = holding period return).

This brings us back to the concept of efficient markets. This theory states that current prices are the best estimate of correct prices at any given time, and that prices change due to:

- New information, and/or

- Changing investor expectations.

It is the combination of these two that is important to remember. It’s not simply enough to know a piece of new information—you must also know how other investors will react to that information. Take our current situation. The market had one of its best weeks ever in the face of unemployment numbers we’ve never seen before. Perhaps the unemployment numbers were better than people expected or perhaps investors were happy that social distancing was actually taking place. Who knows? Volatility is heightened in times like this because of rapid changes in information and expectations and it’s impossible to predict which way the winds are blowing on any given day.

Further posts in this series will explore two more revelations that come from the efficient markets hypothesis:

- It’s very hard to exploit “mispricing”, if not impossible, after accounting for the costs to do so.

- The “market portfolio” is a very efficient portfolio, and you better have a good reason to deviate from it.

Revisiting these fundamentals can give us confidence in our long-term investment plan in the face of whatever environment we find ourselves in.