A few times per year a new company gets a lot of media attention for going public—Airbnb going public next week is the latest. In fact, this year has seen quite a few well-known companies go public with their stock relative to the past decade. I’ve put together a little explainer here about what that entails and whether it’s something we need to be concerned about as long-term investors.

A Brief History of IPOs

An IPO (Initial Public Offering) is the first sale of stock by a company to the public. A company may choose to go public for any number of reasons, but in theory the main purpose is to gain access to a larger pool of capital for further growth and investment (the cynic may say it’s a way for founders and venture capitalists to get a big payout). IPO’s began generating more and more headlines as the dotcom bubble of the late 90’s heated up. Whereas prior to that time a company would only qualify for an IPO with sound financials, the tech boom saw an irrational demand for companies to go public—including many that had yet to even generate revenue!

IPO activity cooled off significantly following the bursting of the tech bubble, but the allure of “striking it rich” has certainly lingered with the financial media. Let’s walk through the case of VA Linux1—a firm that set the then record for first-day price appreciation during the dotcom bubble—to show how this media narrative may not be what it seems. After its first day performance, the Wall Street Journal ran a headline “VA Linux Registers a 698% Price Pop” that offered the following analysis: “Offered at $30 a share, VA Linux exploded to end the day at a 4 p.m. price of $239.25.” So what’s wrong with that? Well, if you were lucky enough to get in at the IPO offering price of $30, then nothing is wrong and you’d have been thrilled with the results. But that’s the rub—it’s extremely difficult to get in at the IPO price.

How Average Investors Get Access to IPOs

When a company is preparing to go public, they need to use an investment bank to help file the proper forms and set the initial price. The investment bank then gets to place the shares with whomever it wants to, basically. If you happen to have an account with the underwriting investment bank, you could theoretically be allocated some shares. As a relatively small investor, someone who isn’t a hedge fund or can’t invest hundreds of millions dollars, who is seeking a “hot” IPO, here’s how it typically works: you ask the bank for IPO shares and then the bank proceeds to ignore your request and move on to larger, more profitable clients.

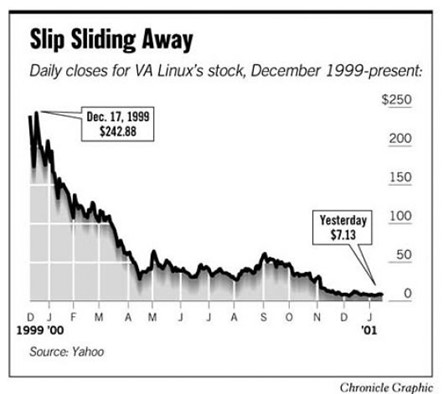

Thus, when we look at what happens to the common investor—that is, the investor who has to buy in through a stock exchange once the IPO shares begin to be publicly traded—we get a muddier picture. For VA Linux, trading opened at $299 (up from the $30 IPO price), went up to $320 and finally closed at $239.25. Thus, if you bought at the opening price in an attempt to participate in this hot IPO, you ended up looking at a 20% loss on the first day of trading. Even in the case where you get in at the IPO price, the headline grabbing first-day returns turn out to be largely irrelevant since you’re typically restricted from trading your shares for a set amount of time (assuming you want to participate in future IPOs). Here’s the chart for VA Linux following the opening day2:

A six month restriction would have seen your shares plummet over 80% off that opening day price before you could do anything.

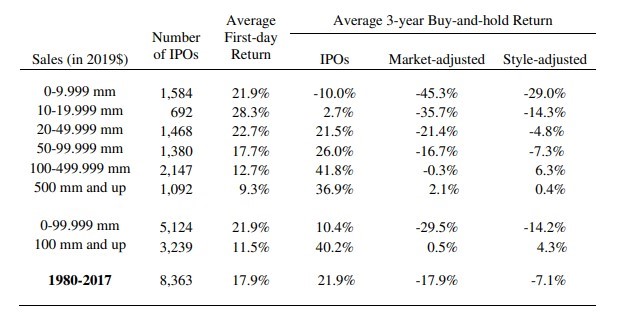

It should come as no surprise that financial headlines aren’t telling the whole truth. In fact, Jay Ritter with the Warrington College of Business has been collecting this data for some time and you can find his most recent paper here. According to that data, here’s what we see for the three years following an IPO:

Looking at the Long Term Results of IPOs

Look at the bottom line. There were 8,363 total IPOs over the 1980-2017 period that returned a total of 21.9% on average for the three years following their debut—a bit over 7% per year. Not bad in a vacuum, but when we compare it to the market as a whole and compare them to stocks with similar characteristics (style-adjusted), we see that they underperform significantly on average. Like any other individual stock picks we remember the winners even though the majority don’t do very well.

None of this is to say I have any idea how Airbnb will perform in the future, but just to remind you that even a highly publicized IPO is still just an individual stock in the end. The exclusivity and chance to “strike it rich” play perfectly for media headlines, which is as good an indication as any that as long-term investors we don’t need to bother ourselves with them.

- I was alerted to this example by a Weston Wellington article from years ago that can be found here. The numbers you’ll see are taken from that article.

- http://www.sfgate.com/business/article/VA-Linux-Easy-Come-Easy-Go-Stock-s-dramatic-2962977.php